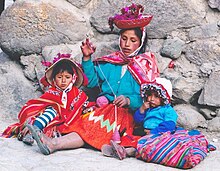

Highland Tribe in South America Highland Tribe of South America and Woman With Baby

An Andean man in traditional clothes. Pisac, Peru. | |

| Full population | |

|---|---|

| 10–eleven one thousand thousand | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| | 6,694,300[1] |

| | 2,056,000[two] |

| | 1,532,200[3] |

| | 154,900[4] |

| | 23,700[five] |

| | 14,000[six] |

| Languages | |

| Quechua • Castilian | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism • Protestantism • Traditional | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Aymaras | |

Quechua people (,[7] [8] United states also ;[nine] Spanish: [ˈketʃwa]) or Quichua people, may refer to any of the aboriginal people of Due south America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are native to Peru, there are some significant populations in Republic of ecuador, Bolivia, Republic of chile, Republic of colombia, and Argentina.

The most common Quechua dialect is Southern Quechua. The Kichwa people of Ecuador speak the Kichwa dialect; in Colombia, the Inga people speak Inga Kichwa.

The Quechua word for a Quechua speaker is runa or nuna ("person"); the plural is runakuna or nunakuna ("people"). "Quechua speakers call themselves Runa -- simply translated, 'the people.'"[ten]

Some historical Quechua people are:

- The Chanka people, who lived in the Huancavelica, Ayacucho, and Apurímac regions of Peru.

- The Huanca people of the Junín Region of Republic of peru, who spoke Quechua before the Incas did.

- The Inca, who established the largest empire of the pre-Columbian era.

- The Chincha, an extinct merchant kingdom of the Ica Region of Republic of peru.

- The Qolla who inhabited the Potosí, Oruro, and La Paz departments of Bolivia.

- The Cañari of Ecuador, who adopted the Quechua language from the Inca.

Historical and sociopolitical background [edit]

The speakers of Quechua, totaling some 5.1 million people in Peru, 1.viii million in Bolivia, ii.five one thousand thousand in Ecuador (Hornberger and King, 2001), and co-ordinate to Ethnologue (2006) 33,800 in Chile, 55,500 in Argentina, and a few hundred in Brazil, accept an only slight sense of common identity. The diverse Quechua dialects are in some cases so different that no mutual understanding is possible. Quechua was non just spoken by the Incas, only also by their long-term enemies of the Inca Empire, like the Huanca (Wanka is a Quechua dialect spoken today in the Huancayo area) and the Chanka (the Chanca dialect of Ayacucho) of Republic of peru, and the Kañari (Cañari) in Republic of ecuador. Quechua was spoken by some of these people, for example, the Wanka, before the Incas of Cusco, while other people, peculiarly in Bolivia but also in Ecuador, adopted Quechua only in Inca times or afterward.[ citation needed ]

Quechua became Peru'southward second official language in 1969 under the infamous dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado. Recently there have been tendencies toward nation building among Quechua speakers, particularly in Ecuador (Kichwa) but also in Bolivia, where at that place are just slight linguistic differences from the original Peruvian version. An indication of this effort is the umbrella system of the Kichwa peoples in Ecuador, ECUARUNARI (Ecuador Runakunapak Rikcharimuy). Some Christian organizations also refer to a "Quechua people", such equally the Christian shortwave radio station HCJB, "The Voice of the Andes" (La Voz de los Andes).[11] The term "Quechua Nation" occurs in such contexts as the name of the Education Council of the Quechua Nation (Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua, CENAQ), which is responsible for Quechua instruction or bilingual intercultural schools in the Quechua-speaking regions of Bolivia.[12] [13] Some Quechua speakers claim that if nation states in Latin America had been built following the European blueprint, they should be a single, contained nation.[ citation needed ]

Material civilisation and social history [edit]

Quechua woman with llamas (Cusco Department, Peru)

Despite their ethnic diversity and linguistic distinctions, the various Quechua indigenous groups accept numerous cultural characteristics in mutual. They besides share many of these with the Aymara, or other Indigenous peoples of the central Andes.

Traditionally, Quechua identity is locally oriented and inseparably linked in each case with the established economic organisation. It is based on agriculture in the lower altitude regions, and on pastoral farming in the higher regions of the Puna. The typical Andean community extends over several altitude ranges and thus includes the cultivation of a variety of abundant crops and/or livestock. The country is usually owned past the local community (ayllu) and is either cultivated jointly or redistributed annually.

Get-go with the colonial era and intensifying after the S American states had gained their independence, big landowners appropriated all or most of the state and forced the Native population into bondage (known in Ecuador every bit Huasipungo, from Kichwa wasipunku, "front door"). Harsh weather condition of exploitation repeatedly led to revolts by the Indigenous farmers, which were forcibly suppressed. The largest of these revolts occurred 1780–1781 under the leadership of José Gabriel Kunturkanki.

Some Indigenous farmers re-occupied their ancestors' lands and expelled the landlords during the takeover of governments by dictatorships in the centre of the 20th century, such as in 1952 in Republic of bolivia (Víctor Paz Estenssoro) and 1968 in Peru (Juan Velasco Alvarado). The agrarian reforms included the expropriation of big landowners. In Bolivia there was a redistribution of the land to the Indigenous population as their individual property. This disrupted traditional Quechua and Aymara culture based on communal ownership, but ayllus have been retained up to the present fourth dimension in remote regions, such as in the Peruvian Quechua customs of Q'ero.

Quechua woman with children

The struggle for land rights continues upward to the present fourth dimension to be a political focal point of everyday Quechua life. The Kichwa ethnic groups of Republic of ecuador which are part of the ECUARUNARI association were recently able to regain communal land titles or the return of estates—in some cases through militant action. Particularly the case of the community of Sarayaku has go well known amongst the Kichwa of the lowlands, who later on years of struggle were able to successfully resist expropriation and exploitation of the rain forest for petroleum recovery.[ commendation needed ]

A stardom is made between ii chief types of joint work. In the case of mink'a, people work together for projects of common interest (such as the construction of communal facilities). Ayni is, in contrast, reciprocal assistance, whereby members of an ayllu help a family to accomplish a large private project, for case business firm construction, and in turn can wait to be similarly helped afterward with a project of their ain.

In almost all Quechua indigenous groups, many traditional handicrafts are an important attribute of cloth civilization. This includes a tradition of weaving handed down from Inca times or earlier, using cotton, wool (from llamas, alpacas, guanacos, vicunas) and a multitude of natural dyes, and incorporating numerous woven patterns (pallay). Houses are usually synthetic using air-dried clay bricks (tika, or in Castilian adobe), or branches and dirt mortar ("wattle and daub"), with the roofs being covered with harbinger, reeds, or puna grass (ichu).

The disintegration of the traditional economy, for example, regionally through mining activities and accompanying proletarian social structures, has usually led to a loss of both ethnic identity and the Quechua linguistic communication. This is also a result of steady migration to big cities (particularly to Lima), which has resulted in acculturation by Hispanic guild at that place.

Foods and crops [edit]

Quechua peoples cultivate and eat a diversity of foods. They domesticated potatoes and cultivate thousands of white potato varieties, which are used for food and medicine. Climate change is threatening their irish potato and other traditional crops only they are undertaking conservation and accommodation efforts.[14] [15] Quinoa is another staple ingather grown by Quechua peoples.[16]

Ch'arki (the origin of the English word jerky) is a Quechua dried (and sometimes salted) meat. It was traditionally made from llama meat that was sun- and freeze-dried in the Andean sun and cold nights, but is now also often fabricated from equus caballus and beefiness, with variation among countries.[17] [18]

Pachamanca, a Quechua word for a pit cooking technique used in Peru, includes several types of meat such as chicken, beef, pork, lamb, and/or mutton; tubers such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, yucca, uqa/ok'a (oca in Spanish), and mashwa; other vegetables such every bit maize/corn and fava beans; seasonings; and sometimes cheese in a small pot and/or tamales.[nineteen] [xx]

Guinea pigs are also sometimes raised for meat.[16] Other foods and crops include the meat of llamas and alpacas every bit well as beans, barley, hot peppers, coriander, and peanuts.[fourteen] [16]

Examples of recent persecution of Quechuas [edit]

Up to the nowadays time Quechuas go along to exist victims of political conflicts and ethnic persecution. In the internal conflict in Peru in the 1980s between the authorities and Sendero Luminoso most 3-quarters of the estimated seventy,000 death cost were Quechuas, whereas the war parties were without exception whites and mestizos (people with mixed descent from both Natives and Spaniards).[21]

The forced sterilization policy nether Alberto Fujimori affected almost exclusively Quechua and Aymara women, a total exceeding 200,000.[22] Sterilization programme lasted for over 5 years betwixt 1996 and 2001. During this menses, women were coerced into forced sterilization.[23] Sterilizations were often performed under dangerous and unsanitary weather, as the doctors were pressured to perform operations under unrealistic authorities quotas, which made it impossible to properly inform women and receive their consent.[24] The Bolivian film director Jorge Sanjinés dealt with the issue of forced sterilization in 1969 in his Quechua-language feature film Yawar Mallku.

Quechuas have been left out of their nation'southward regional economic growth in recent years. The World Banking concern has identified 8 countries on the continent to have some of the highest inequality rates in the globe. The Quechuas take been subject to these severe inequalities, every bit many of them have a much lower life expectancy than the regional average, and many communities lack access to basic health services.[25]

Perceived ethnic discrimination continues to play a role at the parliamentary level. When the newly elected Peruvian members of parliament Hilaria Supa Huamán and María Sumire swore their oath of office in Quechua—for the first time in the history of Republic of peru in an Indigenous linguistic communication—the Peruvian parliamentary president Martha Hildebrandt and the parliamentary officeholder Carlos Torres Caro refused their credence.[26]

Mythology [edit]

Practically all Quechuas in the Andes have been nominally Roman Cosmic since colonial times. Nevertheless, traditional religious forms persist in many regions, blended with Christian elements - a fully integrated Syncretism. Quechua ethnic groups as well share traditional religions with other Andean peoples, peculiarly belief in Mother Earth (Pachamama), who grants fertility and to whom burnt offerings and libations are regularly made. Also important are the mount spirits (apu) every bit well every bit bottom local deities (wak'a), who are withal venerated specially in southern Republic of peru.

The Quechuas came to terms with their repeated historical feel of tragedy in the form of various myths. These include the figure of Nak'aq or Pishtaco ("butcher"), the white murderer who sucks out the fatty from the bodies of the Indigenous peoples he kills,[27] and a song nigh a bloody river.[28] In their myth of Wiraquchapampa,[29] the Q'ero people describe the victory of the Apus over the Spaniards. Of the myths all the same live today, the Inkarrí myth common in southern Peru is especially interesting; it forms a cultural element linking the Quechua groups throughout the region from Ayacucho to Cusco.[29] [30] [31] Some Quechua people consider archetype products of the region - such every bit the Corn beer Chicha, Coca leaves and local potatoes equally having a religious significance, only this belief is not uniform across communities.

Contribution in modernistic medicine [edit]

Quinine, which is constitute naturally in bawl of cinchona tree, is known to be used past Quechuas people for malaria-similar symptoms.

When chewed, coca acts equally a balmy stimulant and suppresses hunger, thirst, hurting, and fatigue; it is too used to convalesce distance sickness. Coca leaves are chewed during work in the fields too equally during breaks in construction projects in Quechua provinces. Coca leaves are the raw fabric from which cocaine, ane of Peru's most historically important exports, is chemically extracted.

Traditional habiliment [edit]

Many Indigenous women wear the colorful traditional attire, consummate with bowler style chapeau. The hat has been worn by Quechua and Aymara women since the 1920s, when it was brought to the land by British railway workers. They are still commonly worn today.[32]

The traditional dress worn by Quechua women today is a mixture of styles from Pre-Spanish days and Castilian Colonial peasant wearing apparel. Starting at puberty, Quechua girls begin wearing multiple layers of petticoats and skirts; the more petticoats and skirts worn by a immature woman, the more than desirable a bride she would be, due to her family'southward wealth (represented past the number of petticoats and skirts). Married women too wear multiple layers of petticoats and skirts. Younger Quechua men generally wear Western-way clothing, the most popular existence synthetic football game shirts and tracksuit pants. In certain regions, women likewise generally clothing Western-style clothing. Older men still wear dark wool articulatio genus-length handwoven bayeta pants. A woven belt called a chumpi is also worn which provides protection to the lower back when working in the fields. Men's fine dress includes a woollen waistcoat, similar to a sleeveless juyuna equally worn past the women but referred to as a chaleco. Chalecos tin can exist richly decorated.

The almost distinctive part of men'south clothing is the handwoven poncho. Nearly every Quechua man and boy has a poncho, more often than not red in colour busy with intricate designs. Each commune has a distinctive pattern. In some communities such as Huilloc, Patacancha, and many villages in the Lares Valley ponchos are worn equally daily attire. Still most men use their ponchos on special occasions such equally festivals, village meetings, weddings etc.

Every bit with the women, ajotas, sandals made from recycled tyres, are the standard footwear. They are cheap and durable.

A ch'ullu is oft worn. This is a knitted hat with earflaps. The first ch'ullu that a child receives is traditionally knitted by his father. In the Ausangate region chullos are oft ornately adorned with white chaplet and large tassels called t'ikas. Men sometimes wear a felt hat called a sombrero over the tiptop of the ch'ullu decorated with centillo, finely busy hat bands. Since ancient times men have worn small woven pouches called ch'uspa used to carry their coca leaves.[33]

Quechua-speaking ethnic groups [edit]

Distribution of Quechua people in Bolivia among the municipalities (2001 national census).

Quechua adult female (Puruhá), Ecuador, neighborhood of Alausí (Chimborazo province)

The following list of Quechua ethnic groups is only a selection and delimitations vary. In some cases these are village communities of just a few hundred people, in other cases ethnic groups of over a million.

- Inca (historic)

Peru [edit]

Lowlands

- Quechuas Lamistas

- Southern Pastaza Quechua

Highlands

- Huanca

- Chanka

- Q'ero

- Taquile

- Amantaní

- Anqaras

- Huaylas

- Piscopampas

- Huaris

- Sihuas

- Ocros

- Yauyos

- Yarus

Ecuador [edit]

- Amazonian Kichwas

- Otavalos

- Salasaca

Bolivia [edit]

- Kolla

- Kallawaya

Gallery [edit]

Notable people [edit]

- Túpac Amaru II, Revolutionary

- Angélica Mendoza de Ascarza, Human rights activist

- Benjamin Bratt, Peruvian-American actor

- Manco Cápac, Sapa Inca

- Martín Chambi, Photographer

- Edison Flores, Footballer

- Oswaldo Guayasamín, Ecuadorian painter

- Ollanta Humala, President of Peru

- Josh Keaton, Peruvian-American histrion

- Q'orianka Kilcher, Actress

- Magaly Solier, Actress

- Diego Quispe Tito, Painter

- Alejandro Toledo, President of Peru

- Juan Manuel Vargas, Footballer

- Yoshimar Yotún, Footballer

- Francisco Tito Yupanqui, Sculptor, Saint

See also [edit]

- Kichwa

- Inkarrí

- Yanantin

- Sumak Kawsay

- Andean textiles

- Chuspas

- Chakitaqlla

- Chinchaypujio District

References [edit]

- ^ https://joshuaproject.internet/countries/PE

- ^ https://joshuaproject.net/countries/BL

- ^ https://joshuaproject.net/countries/EC

- ^ https://joshuaproject.cyberspace/countries/AR

- ^ https://joshuaproject.net/countries/CO

- ^ https://joshuaproject.net/countries/CI

- ^ "Quechua - meaning of Quechua in Longman Lexicon of Contemporary English". Ldoceonline.com . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Oxford Living Dictionaries, British and World English

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (third ed.), Longman, ISBN9781405881180

- ^ "Language in Republic of peru | Frommer's".

- ^ CUNAN CRISTO JESUS BENDICIAN HCJB: "El Pueblo Quichua".

- ^ "CEPOs". Cepos.bo. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ [1] [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ a b "Climatic change Threatens Quechua and Their Crops in Peru'southward Andes - Inter Press Service". Ipsnews.net. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "The Quechua: Guardians of the Potato". Culturalsurvival.org . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b c "Quechua - Introduction, Location, Language, Sociology, Religion, Major holidays, Rites of passage". Everyculture.com . Retrieved 26 Baronial 2018.

- ^ Kelly, Robert Fifty.; Thomas, David Hurst (i January 2013). Archaeology: Down to Globe. Cengage Learning. pp. 141–. ISBN978-1-133-60864-6.

- ^ Noble, Judith; Lacasa, Jaime (2010). Introduction to Quechua: Language of the Andes (2nd ed.). Dog Ear Publishing. pp. 325–. ISBN978-one-60844-154-9.

- ^ "Peru'due south Pitmasters Bury Their Meat in the World, Inca-Fashion". Npr.org . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Oca". Food and Agronomics Organization of the United nations . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Orin Starn: Villagers at Arms: War and Counterrevolution in the Central-South Andes. In Steve Stern (ed.): Shining and Other Paths: War and Lodge in Peru, 1980–1995. Duke University Press, Durham und London, 1998, ISBN 0-8223-2217-10

- ^ [ii] [ dead link ]

- ^ Carranza Ko, Ñusta (4 September 2020). "Making the Case for Genocide, the Forced Sterilization of Indigenous Peoples of Peru". Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal. 14 (2): 90–103. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.two.1740. ISSN 1911-0359.

- ^ Kovarik, Jacquelyn (25 August 2019). "Silenced No More in Republic of peru". NACLA Report on the Americas. 51 (3): 217–222. doi:10.1080/10714839.2019.1650481. ISSN 1071-4839. S2CID 203153827.

- ^ "Discriminated against for speaking their own linguistic communication". Earth Bank . Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Archivo - Servindi - Servicios de Comunicación Intercultural". Servindi.org . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Examples (Ancash Quechua with Spanish translation) at "Kichwa kwintukuna patsaatsinan". Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2009. and (in Chanka Quechua) "Nakaq (Nak'aq)". Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ Karneval von Tambobamba. In: José María Arguedas: El sueño del pongo, cuento quechua y Canciones quechuas tradicionales. Editorial Universitaria, Santiago de Republic of chile 1969. Online: "Runasimipi Takikuna". Archived from the original on v June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (auf Chanka-Quechua). German translation in: Juliane Bambula Diaz and Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, p. 172

- ^ a b Thomas Müller and Helga Müller-Herbon: Die Kinder der Mitte. Die Q'ero-Indianer. Lamuv Verlag, Göttingen 1993, ISBN 3-88977-049-v

- ^ Jacobs, Philip. "Inkarrí (Inkarriy, Inka Rey) - Q'iru (Q'ero), Pukyu, Wamanqa llaqtakunamanta". Runasimi.de . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Juliane Bambula Diaz und Mario Razzeto: Ketschua-Lyrik. Reclam, Leipzig 1976, pp. 231 ff.

- ^ "La Paz and Tiwanaku: colour, bowler hats and llama fetuses - Don't Forget Your Laptop!". x September 2011. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 26 Baronial 2018.

- ^ "My Peru - A Guide to the Culture and Traditions of the Andean Communities of Peru". Myperu.org . Retrieved 26 August 2018.

https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/grupos-etnicos/presentacion-grupos-etnicos-2019.pdf[ane]

External links [edit]

- Quichua, Peoples of the World Foundation

- World Directory of Minorities and Ethnic Peoples - Bolivia : Highland Aymara and Quechua, UNHCR

- ^ kinvty, hector (2020). "inga y KICHWA" (PDF).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quechua_people

0 Response to "Highland Tribe in South America Highland Tribe of South America and Woman With Baby"

Post a Comment